shadowslongshoreman by José Daniel García

De los muchos extranjeros que han escrito sobre Colombia -desde Von Humboldt hasta Wade Davis- pocos han tenido tanto éxito comercial como el historiador David Bushnell, pues se está vendiendo la séptima décima edición de Colombia: una nación a pesar de sí misma, resultado de sesenta años de investigación del estadounidense de la historia colombiana.

Su interés en el país empezó como estudiante de pregrado en Harvard, en la década de los años 30. Colombia, en esa época, era una anomalía en Latinoamérica: según algunos, porque nunca tuvo un caudillo. Como explica el Dr. Bushnell, la democracia lo trajo al país; sin embargo, durante todos sus años de ida y vuelta a Colombia jamás había sido testigo de un proceso electoral en persona hasta el momento que nos conocimos en 2010. El tema que le fascinaba. Como conferencista invitado al Foro Alfonso López Pumarejo en Bogotá, el Dr. Bushnell estaba feliz de volver a la ciudad capitalina, donde llegó por la primera vez en 1944, cuando era un joven historiador idealista, cuando aún no usaba el bastón y tomaba la tranvía. Charlamos con él una fría y lluviosa tarde, degustando una humeante sopa de ajiaco – su plato colombiano favorito – acompañada por una cervecita.

Lo que no yo no sabía era que Bushnell sólo viviría unos meses más antes de su muerte en septiembre del mismo año. Lo que sigue es el transcripción de aquella tarde de 2010.

Yo: ¿Cómo le fue en la conferencia de Alfonso López Pumarejo?

David: Pues vinieron varios candidatos presidenciales. Pardo y Mockus, con su vice. Pardo era mucho más organizado.

Yo: Mockus es más idiosincrático…

David: ¿Pardo se bajaría los pantalones al frente del congreso? No creo.

Yo: Supongo que no. (Risas) Usted vino a Bogotá en el 48. ¿Vio el Bogotazo?

David: No, llegué en junio. Originalmente, planeaba venir a medios de mayo, pero no entregaban visas mientras el país se calmaba. Sin embargo, en junio todavía había toque de queda, pero fuera de eso las cosas estaban más o menos normales. Pero nunca había visto en persona un día de elecciones.

Yo: ¿Cómo le ha parecido?

David: Muy distinto a las elecciones en los Estados Unidos. Claro, hay carteleras y mucha mención en los periódicos. Pero el hecho de que Uribe no se hubiera decidido a lanzarse a la reelección y que la corte no hubiera tomado parte, sino hasta hace poco, las afectó. No es una elección normal, digamos, ni para Colombia.

Yo: ¿Por quién votaría?

David: Probablemente, Pardo. Estaría feliz con Antanas. Es más un asunto de tradición, siendo un liberal por muchos años, y además porque descubrí la existencia de Colombia en los años 30 y 40, los años dorados de la Colombia liberal y demócrata, hay un poco de añoranza por mi parte. Cualquiera de los dos sería interesante.

Yo: Vi que en la primera vuelta la intención de voto mostraba empatados a Pardo y Santos.

David: Asumo que en la segunda vuelta mucha gente creará alianzas contra Santos. Pardo, por ejemplo, no va a apoyar a Santos. Pero los votantes hacen lo que quieren de todas formas. Yo no apoyaría a Santos. Por otro lado ¿dónde están los campesinos, los terratenientes? Ellos obviamente van a apoyar a Santos. ¿Uno puede ser presidente sin el apoyo de estos grupos? Será interesante ver cómo sale.

Yo: ¿Qué opina de uribismo? ¿Qué hizo por Colombia?

David: Yo creo que lo verán en los libros de historia como uno de los presidentes buenos, a pesar de sus flaquezas. Hacía falta algo como la seguridad democrática. Claro, también es malgeniado; ha salido con unas cosas muy extrañas.

Yo: ¿Cómo se veía Colombia cuando estaba estudiando en Harvard?

David: Realmente la gente no sabía mucho de Latinoamérica. En los 30 y 40 obviamente los asuntos internacionales tenían mucho que ver con sus percepciones. Colombia fue visto como aliado, uno de los ¨buenos¨ en el equipo internacional, en parte porque el gobierno realmente creía en los objetivos de los buenos, a pesar de que no fueran regalados como Somoza, por ejemplo. López y Santos realmente creían en la democracia en contra de los nazis y los socialistas. Era un país libre a diferencia de muchos de sus vecinos. No era una democracia perfecta, pero no existe tal cosa. Había Colombia y Costa Rica, y ya. No hubo muchas democracias que funcionan en esa época. Eso me llamó la atención.

Yo: ¿Cómo se interesó en historia?

Yo: ¿Cómo se interesó en historia?

David: Estaba en Harvard en los 40 con un interés en Latinoamérica. Iba a estudiar ciencia política, y no la ofrecían. Tenía Spanish como área de concentración, pero su época de oro fue cuando el poeta Longfellow [del siglo XIX] dictaba español, y no era tan bueno para empezar. No obstante, tenía un puesto otorgado de historia. Yo me inscribí en todos los cursos. El curso que ofrecía sobre historia latinoamericana lo dictaba un historiador español, en lo que pasamos la mitad del semestre escuchando sus antecedentes en España. Lo bueno de historia es que cubre todo.

Yo: ¿Ha cambiado la forma en que Estados Unidos percibe a Colombia?

David: Pues la opinión de Latinoamérica en los EEUU nunca ha sido tan buena. Durante la guerra hubo mucho alarmismo. Su interés sobre todo era, están con nosotros o no están con nosotros: primero con los nazis, después con los soviéticos. En el caso de Colombia, una de las razones porque hubo interés, era su cercanía al canal. Una de las razones por las que convirtieron SCADTA a Avianca era para deshacerse de esos pilotos alemanes. SCADTA fue fundado en Barranquilla por la colonia alemana y algunos colombianos, pero la mayoría eran alemanes. Tuvieron mucho éxito. En los 30, Panam, que en esa época era enorme, les molestaba SCADTA metiéndose en el mercado mundial. Panam empezó a comprar la mayoría de su stock. A ellos no les importaba el canal, ni los alemanes, simplemente no querían que se volaran las rutas latinoamericanas y la competencia. Durante la guerra los presionaron, creando Avianca.

Yo: ¿Cómo llegó a escribir Colombia: una nación a pesar de sí misma?

David: Hubo una necesidad en ese tiempo. Hasta ese punto faltaba un buen texto de la historia colombiana en inglés. Solo había una traducción del clásico de Urugula. Sigue siendo útil, si uno necesita saber quien fue presidente en 1872, lo encuentra allí. Yo dictaba un curso en la Florida sobre la gran Colombia, que era más Colombia que ninguna otra cosa. La mayor parte de ese libro consiste en las notas de esas clases. Yo creo que el hecho de que provenga de esas clases le imprime un estilo distinto. Sin embargo, las clases no cubrían todo, entonces también fue una obra de la palabra escrita.

Yo: ¿Cuándo fue eso?

David: Más o menos en los 70. Ya había dictado el curso varias veces, puliendo las notas, etc.

Yo: Uno de los puntos de su libro parece expresar que durante periodos de violencia hay prosperidad…

David: Pues en los 80 sí, pero no en toda la historia, antes de siglo XX la economía era muy subdesarrollada.

Yo: ¿Por qué cree que Colombia no tuvo un caudillo?

David: Tal vez la debilidad del ejército tenía que ver -que no es el caso hoy en día- sobre todo con el predominio de venezolanos en las fuerzas armadas en la Gran Colombia. A la clase dominante, la oligarquía o lo que fuera, no les convenìa un caudillo. En Colombia fueron capaces de hacer lo que quisieron sin una dictadura.

Yo: En su libro compara a Rojas Pinilla con Perón…

David: Pues los dos eran militares, aunque de ejércitos distintos. Rojas en los 50 no triunfó, usando más o menos un modelo peronista. Solo que aquí el movimiento obrero estaba dividido, que Pinilla dividió aún más, mientras Argentina era fuertemente peronista. También la iglesia se ofendió con su acercamiento a Perón; sus seguidores no respetaban mucho a la iglesia. En esa época hubo también muchas diferencias en niveles de desarrollo industrial.

Yo: ¿Usted cree que el cobalto afectará el desarrollo en Colombia?

David: Leí algo sobre eso. No sé. Yo leo Semana. Desde el deceso de Cambio, subscribirse en el extranjero vale el doble. Creo que me va a tocar leerlo en línea. No creo que lo vaya a renovar. Otra secuela de la persecución de Cambio. Semana siempre ha dado más información que Cambio. Ahora creo que me metería en Semana.com y todo está ahí. Sin embargo me gusta leer en el papel.

El bicentenario parece cubrir todo. Está esa conferencia de Alfonso López que de alguna manera era parte del bicentenario. El otoño pasado en Cartagena hubo un foro que también era parte del bicentenario, a pesar de que tomara lugar el año pasado.

Yo: Ha escrito mucho sobre Simón Bolívar. ¿Qué opina del uso de su imagen cómo figura de independencia? ¿es válido?

David: Él era el número uno para toda Latinoamérica. Claro que era un genio. No fue tan buen presidente, pero eso es otro cuento. Tenía una mente original. Tenía muchas ideas originales. Era un pensador original al contrario de Santander, por ejemplo. Bolívar soñó sus propios sueños. Un comunicador maravilloso. Solo leer Bolívar es un placer. Su carrera cubre casi toda Latinoamérica. Está en una clase de sí mismo. Cuando quieren promocionar a Latinoamérica buscan a Simón Bolívar, como Chávez recientemente, el ejemplo obvio. Pero en los 50 en Colombia también se utilizó su imagen. En la época de Laureano Gómez cuando el partido conservador era fuerte, vieron a Bolívar como el precursor de un líder fuerte, pro católico y demócrata. Demócrata, sí. ¿Católico? No.Iba a misa para leer. Uno de sus socios europeos, un soldado muy buen amigo, que sacaba un volumen de Voltaire durante la misa. No encontrará eso en El Siglo de esa época.

Yo: ¿Qué opina de Chávez? ¿El chavismo?

David: No dudo que haya hecho algunas cosas buenas, aunque con todo ese dinero es difícil no hacer algo bueno. Su récord en derechos humanos no es tan bueno, pero no es dictador todavía. Claro que sus ideas sobre la historia están un poco locas.

Yo: ¿Por ejemplo?

David: Cuando hace dos años quería exhumar el cadáver de Bolívar a ver si lo habían envenenado los santanderistas en Santa Marta. En todos mis años jamás he escuchado un asesinato por veneno. Le disparan. Lo apuñalan. El veneno es tan renacimiento, tan Roma antigua. Todo es solo para que pareciera que los colombianos lo asesinaron, a pesar de que huyera de Venezuela, y por eso murió en Colombia.

Yo: ¿Usted cree que provocará una guerra?

David: Chávez no es tan estúpido. Él sabe quién está con los colombianos. Lo que puede hacer es dar ayuda clandestina a los guerrilleros, pero no lo suficiente como para mantenerlos.

Yo: ¿Es la violencia algo colombiano?

David: Creo que es algo de los intelectuales colombianos. Creo que los intelectuales colombianos distorsionan la historia colombiana. ¿Usted lee a Eduardo Posada?

Yo: No.

David: Pues es un columnista en El Tiempo. Escribió el libro El país que soñamos que ataca a los intelectuales aquí, poniendo todo en términos negativos. Cuentan una historia de violencia continua. La historia colombiana no carece de violencia. Como lo expuso Uribe ayer en su conferencia, cada vez que Colombia parecía que iba bien, estallaba en violencia. Pero entre esas épocas, el país era relativamente pacífico. Si uno mira las crónicas de los viajeros en el siglo XIX, verá extranjeros impresionados de que el correo podía viajar entre pueblos sin protección, ni escolta. No hubo muchos problemas de crimen. Claro que hubo guerras civiles. Y eso no es bueno. Pero las fuerzas involucradas y las bajas eran pocas. El daño fue más a la estima del país, haciendo las cosas imprevisibles. La guerra de los mil días fue un desastre, aunque no afectó al país entero, como la Violencia que fue igualmente severa en todas partes. Hasta los 40 fue un país pacífico. Muchos de esos problemas no son colombianos. La violencia no es un invento colombiano. La corrupción no es un invento colombiano. Además ¿cuántos presidentes colombianos han acumulado fortunas en cuentas bancarias en las islas Caimán o en Portugal? Yo no conozco ninguno. Los altos rangos del gobierno han sido más o menos limpios en los últimos años, mucho más que Venezuela.

Yo: ¿Doscientos años después cómo ve a Colombia?

David: Se ve mejor que hace doscientos años. Fue un país un poco más pacífico bajo el dominio de España. Pero en términos de desarrollo, estuvo de últimas en la clase. Se han visto muchas mejoras desde entonces. Una cosa que yo diría en su bicentenario, su sistema político aunque no es perfecto, la mayoría de las veces es funcional, con elecciones. Eso se basa en los primeros años de la república, la presunta ´patria boba´, donde uno ve elecciones tras elecciones. Aquello creó un estilo de política que lo separa del resto de Latinoamérica donde han tenido muchas interrupciones largas. La más larga interrupción en la historia de la democracia colombiana fue bajo el gobierno de Rojas Pinilla.

Yo: ¿Algunos señalan el Frente Nacional como el origen de los problemas del siglo XX?

David: El Frente Nacional fue sobre todo un paso adelante de la Violencia. La noción de que el Frente Nacional abolió la competencia política es una pura bobada. Un comunista podía salir en el partido liberal. Nadie estaba verificando credenciales. Uno fue liberal un día del año y comunista el resto. Rojas Pinilla, por ejemplo, casi gana la presidencia durante el Frente Nacional. La crítica más válida es que los dos partidos no tenían que competir. Esa fue la excusa que dió la guerrilla por muchos años: competir no ganaba nada, y por eso se armaban. En fin, son las armas las que no ganan nada, menos una tumba.

Yo: ¿Y el futuro?

David: Siempre he sido optimista. Para ser un colombianista en los 50 yo tenía que ser optimista. Siempre quería ver un mejor resultado y creo que lo tenemos, aunque hay mucho trabajo que hacer, gane Santos, o gane Mockus, o si de repente, Noemi sube. Me gustaría ver una presidenta. Si después de todos sus errores puede hacer campaña, quién sabe.

En 2003 la editorial McSweeney’s publicó una edición limitada de Rising Up, Rising Down, de William T. Vollmann, una exploración ensayística extensa de la violencia. En dos de los siete volúmenes, Vollmann narra su experiencia en Colombia: en 1999 en El Cartucho, una de las zonas social y económicamente más deprimidas de Bogotá, y en 2001 en Honda, Tolima.

Compré Rising Up, Rising Down usado por cien dólares. Leí los primeros cuatros volúmenes antes de establecer residencia en Colombia. Poco después descubrí sus aventuras colombianas en los tres libros de crónicas, divididos por continentes y titulados, ¨Secuelas de la violencia¨. Sus crónicas en las Américas incluyen a Jamaica, a los Estados Unidos y a Colombia – los lugares más violentos en el momento. Muchos de los escritos ya se habían publicado en revistas como Harper´s y Esquire.

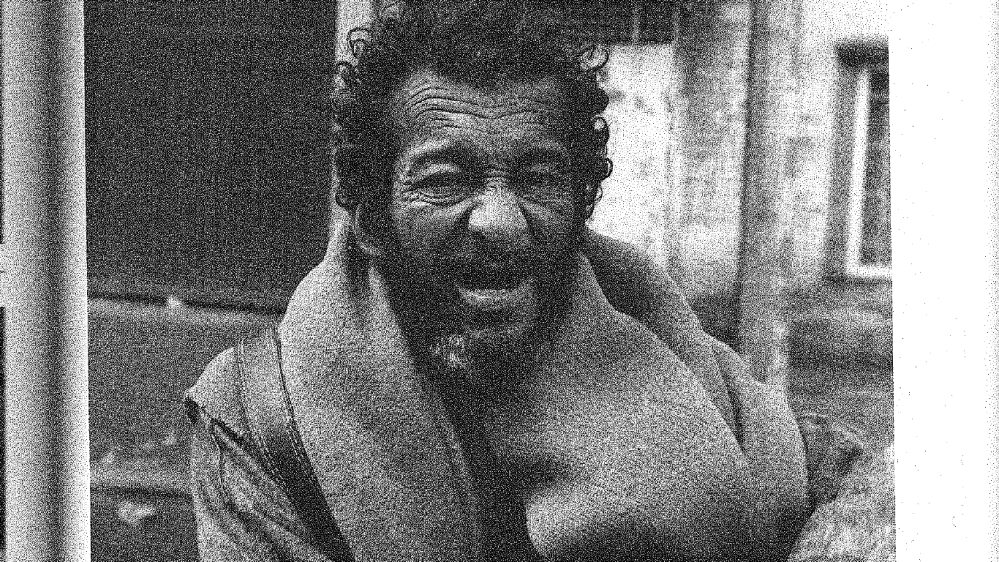

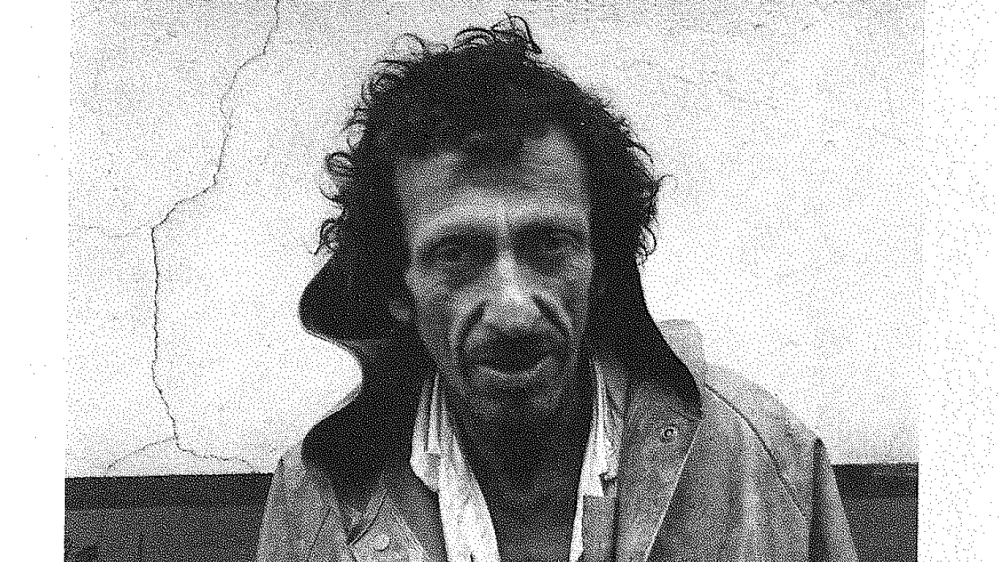

En 2001, Colombia tenía la tasa de homicidios per cápita más alta del mundo. Una visita al país para el estudio de este fenómeno debía haber parecido obligada. De sus dos viajes al país, relata que pasó sus días entre filas de paramilitares y ofrece una detallada explicación del basuco antes de fumarlo. Además tomó fotos escalofriantes de las poblaciones más vulnerables del país en la época.

Poco después de llegar a Colombia comencé a leer la revista El Malpensante. De hecho, me llegó una colección de las primeras cien ediciones. Quería escribir para la revista y un perfil de Vollmann me parecía una buena idea. Tenga en cuenta que jamás había escrito para una revista ni había hecho entrevistas. Contacté a su agente quien me explicó, “La única manera de contactar a Bill es por el teléfono o por el correo y es muy difícil por aquel medio; a él no le gusta dar su número telefónico y siempre está ocupado”.

Pero muy amablemente, me ofreció la opción de mandar mis preguntas por email y que ella podría entregárselas y después devolvérmelas .

Debo decir que también me gustaba la ficción de William T. Vollmann y sin ser obsesivo con el escritor estadounidense, yo sí era un fanático. Recibir sus palabras en un documento en Word me llenó de entusiasmo.

Casi diez años después de este suceso, mi ingenuidad periodística -con una cadena de preguntas sin ton ni son- es obvia. En parte prefiero no recordarlo, pero siendo la única entrevista que William T. Vollmann hizo sobre Colombia, me siento obligado a publicarla, aunque sea en un blog.

J.T.M: ¿Por qué escribe?

J.T.M: ¿Por qué escribe?

W.T.V: Porque me da satisfacción, alegría y consolación y porque espero poder hacer una diferencia.

J.T.M: Cómo describiría su obra?

W.T.V: Variada.

J.T.M: ¿Dónde se ubica en su carrera?

W.T.V: La parte media tardía.

J.T.M: También es fotógrafo. ¿Cuál es la relación entre susfotografías y su obra escrita?

W.T.V: Las fotografías complementan la escritura documentalista en cuanto a que ayuda al lector a ver y así creer. Además, las fotografías permiten al lector y a mí, ver en nuestro tiempo libre lo que de pronto no se pudo ver en algún otro momento. Algunas de las fotos más tristes que he tomado son las de colombianos desplazados por la violencia. Muchos de los negativas estuvieron guardados en mis archivos por una década. Ahora estoy imprimiendo un portafolio de retratos de refugiados. Algunas de las expresiones de las personas de quienes tomé fotos en 1999 y 2000 son casi insoportables. .

J.T.M. En cuanto a sus viajes, muchos de los escritores estadounidenses que han estado “al otro lado son muy machos, pero usted no. ¿Cómo se describe usted a sí mismo como escritor?

W.T.V: Honestamente, quiero aprender qué es la realidad y, mientras tanto, ayudar a las personas que conozco por el camino.

J.T.M: En su libro sobre viajar en los trenes de transporte confiesa estar harto de los EE.UU. ¿Usted cree que algo cambiará con la reciente victoria de Obama?

W.T.V: Obama me da esperanzas de que mi gobierno deje de torturar a la gente. Es un toque más conservador para mi gusto, pero voté por él porque parecía mucho más iluminadoque la alternativa. Me complace mucho que se acerca a otros países sin arrogancia. Por otro lado, sus políticas con Iraq, Afganistán y la marihuana, entre otros temas, son tímidas.

J.T.M: Cuando leí Los pobres pensé en la obra de Immanuel Wallerstein. ¿Usted está de acuerdo con sus hallazgos? ¿Cómo son distintos en términos de metodología?

W.T.V: No conozco la obra de Wallerstein suficiente para comentar.

J.T.M: Usted vino a Colombia cuando era uno de los lugares más violentos del planeta. ¿Por qué piensa que fue violento?

J.T.M: Usted vino a Colombia cuando era uno de los lugares más violentos del planeta. ¿Por qué piensa que fue violento?

W.T.V: A mí me parece que la violencia en Colombia se deriva de diferencias ideológicas duraderas muchas veces relacionadas con la clase. La gente que expresa esas diferencias en la praxis de violencia ha establecido bases para sí misma a lo largo del tiempo. Una de las fuentes principales de lucro es el narcotráfico. Gracias en parte a la miope “guerra contra drogas”, que ligeramente reduce la oferta sin reducir la demanda, el narcotráfico es muy lucrativo – tanto que los motivos ideológicos se aumentan por avaricia. La débil autoridad gubernamental lo empeora. He entrevistado a policías con miedo a alejarse de sus sitios de trabajo… Y así los asesinos pueden operar como quieran, más o menos, sujetos sólo a la fuerza de sus rivales. Uno de los fenómenos más horrorosos de esto es la manera como la gente inocente puede ser reclutadado un modo u otro, por un lado a punta de pistola, después de que, por otro lado, el otro grupo quiere castigarla.

(Por cierto, estoy hablando en el presente, pero no he visitado su país desde 2000; disculpe por favor lo que sea anticuado.)

J.T.M: En Rising Up, Rising Down, comenta que no había estado en un país tan listo para una revolución como Colombia. ¿Por qué cree que aquella revolución nunca llegó a pasar?

W.T.V: Vendrá.

J.T.M: ¿Cuáles son sus autores latinoamericanos favoritos ? ¿Y colombianos? ¿Sus obras favoritas? ¿Los usó en su investigación de Rising Up, Rising Down?

W.T.V: Márquez es mi autor latino favorito de todos los tiempos. Claro que amo Cien años de soledad. Leí Crónica de una muerta anunciada y me dejó triste e impresionado. No lo usé en mi estudio sobre la violencia.

J.T.M: Quizá conoce el término ‘la violentología’, una área de la sociología enfocada en la violencia. Usted considera Rising Up, Rising Down una investigación violentóloga?

W.T.V: Sí.

J.T.M: El Plan Colombia, el programa de apoyo monetario al ejército colombiano para combatir a los otros actores armados, ha sido punto de muchas críticas. ¿Cómo ve usted esta política?

W.T.V: Parece que no puede ser exitosa. La mayoría de la gente en el ejército colombiano es intrínsecamente decente, como la mayoría de la gente en cualquier lado. Pero se le paga muy poco y su control es limitado. ¿Cómo se puede aspirar a igualar el poder de la gente con nexos con el narcotráfico? Algunas personas del ejército, creo, se han involucrado con el narcotráfico, pero eso no puede adelantar los objetivos nacionales. Además, mi impresión es que la ayuda estadounidense es parcial (por ejemplo, mi gobierno no es muy parcial a las FARC). En pocas palabras ¿qué ímpetu tiene la gente que no está en la mesa de negociación a dejar las armas? Ni siquiera se les puede sobornar, dado que el dinero de las drogas es seguramente más abundante que el dinero del gobierno estadounidense. Finalmente, considero que el uso de los defoliantes fumigados para eliminar la coca son contraproducentes desde una perspectiva social y ecológica, dado sus consecuencias en cuanto a la salud y el medio ambiente.

J.T.M: El otro tema de debate en la relación de Colombia con los Estados Unidos ha sido el Tratado de Libre Comercio. Muchos senadores, incluso Nancy Pelosi, han mostrado su oposición al acuerdo, citando el asesinato de líderes sindicales y líderes de movimientos sociales. ¿Cree que se debe abrir un acuerdo de intercambio entre los dos países?

W.T.V: No entiendo el tema suficiente para tener una opinión. En México, muchos parecen haber empobrecido por el NAFTA. Por ejemplo, leí sobre unas granjas de lácteos que no no pueden competir con la leche importada de los EE.UU. Así que no puedo decir si fuese favorable para Colombia.

J.T.M: Tal vez ha escuchado que las tensiones entre Ecuador, Venezuela y Colombia se han complicado con el asesinato de Raúl Reyes en la frontera con Ecuador. Según su cálculo moral, ¿fue justificado?

W.T.V: Para contestar esto, tendría que ir a la zona y escuchar a algunas personas.

J.T.M: En el pasado ha dicho que la gente pobre es el resultado de sistemas jurídicos deficientes.. Con la tasa de pobreza en Colombia, ¿opina que el sistema es inadecuado?

W.T.V: No he investigado suficiente el sistema legal en Colombia, pero me imagino que la autoridad policíaca es débil, la autoridad de los magistrados y los abogados debe ser más débil aún.

J.T.M: Cuando vino a Bogotá se quedó en una zona conocida como El Cartucho. No sé si se ha enterado que fue demolido y encima construyeron un parque. Cómo ve este tipo de intervención urbana?

W.T.V: El Cartucho era un lugar aterrador. Me encantaría que esa zona fuese más segura hoy. Pero también espero que a las personas cuyas casas habrán sido destruidas, les hayan dado otras casas.

J.T.M: Ha escrito mucho sobre las prostitutas. ¿Conoció algunas en Colombia? ¿Cómo se distinguen de las de otros países?

W.T.V: Sí, conocí a algunas personas y tomé sus fotos. Una diferencia que noté era que en algunos lugares, por ejemplo en algunas zonas de Bogotá, las puertas donde las prostitutas se mostraban tenían rejas o persianas metálicas.

J.T.M: Hay una tendencia, sobre todo en los países en desarrollo, de documentar lo que unos llaman “pornomiseria”. Algunos podrían ver su obra en ese sentido. ¿Cómo distingue usted su obra de la llamada “pornomiseria”?

W.T.V: Vine a Colombia con el deseo sincero de aprender. Espero que una persona lea Rising Up, Rising Down y aprenda algo o, mejor aún, se conmueva para ayudar a colombianos que lo necesiten. También espero que los lectores de RURD vean que los colombianos en general no son necesitados. Los colombianos son increíblemente cariñosos. Nunca había hecho amigos tan fácilmente como en Colombia. Hay gente en Colombia que ha hecho mucho por mí. Sus médicos, sus policías y sobre todo sus periodistas – para no mencionar la gente a quien conocí de casualidad en sus casas – pueden ser increíblemente valientes. Su paisaje es espectacularmente lindo. Las mujeres colombianas son fascinantes. Muchas personas son especialmente generosas.

J.T.M:Viajando por el mundo hispanoparlante, muchos me preguntan qué autor estadounidense les recomendaría. El primero que nombro suele ser usted. Sin embargo, he encontrado que poco de su obra ha sido traducido. ¿Por qué cree que eso sea así?

W.T.V: No sé. Tal vez mis libros no fueron lo suficientemente buenos.

J.T.M: ¿Aparece Latinoamérica en su ciclo Siete Sueños? ¿Cómo ve la historia de Norteamérica con su vecino del sur?

W.T.V: Latinoamérica aparece sólo periféricamente en el ciclo Siete Sueños dado que es una obra de “paisajes norteamericanos”.

Here are highlights from my reading as I remember it. This list mostly reflects my own idiosyncratic taste – so not really a “best” more like memorable favorites.

My Struggle (Books 1-5)

I actually read about Karl Ove Knausgaard in a Colombian magazine, before he visited the Hay Festival in Cartagena. I’ve enjoyed reading Norwegian literature in translation ever since a class I had with Saul Bellow and John Woods with Knut Hamsun’s Hunger. I hadn’t read a book of Norwegian lit for some time.

I can’t say exactly what it is about Knausgaard’s series that speaks to me. (There is a the heteronormative male element of course.) Just when one of the books grows boring, a shocking, even traumatic event arises and I continue to read. Sometimes I’m simply surprised by what Knausgaard will narrate (the vomit-ridden coitus in Volume III comes to mind). I eagerly await the next volume to be translated to English.

La forma de las ruinas

While I’ve enjoyed everything I’ve read by Juan Gabriel Vasquez, La forma de las ruinas takes many elements present in previous novels – the role of history in our live, Conradesque narration within narration, being a foreigner – and painstakingly translates them in the personal dimension.

While I’ve enjoyed everything I’ve read by Juan Gabriel Vasquez, La forma de las ruinas takes many elements present in previous novels – the role of history in our live, Conradesque narration within narration, being a foreigner – and painstakingly translates them in the personal dimension.

This has all of the feel of a magnum opus.

This graphic novel experiments with narration and research in such a way, it’s hard to deny its power and scope over a region – Montes de Maria- deeply affected by the armed conflict in Colombia.

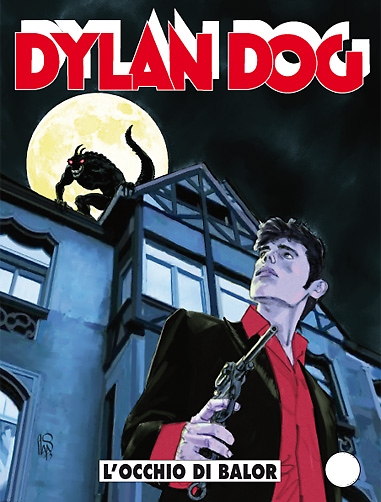

Dylan Dog

Italophiles will have known this graphic novel star intimately, Tiziano Sclavi’s comic book hero who is a stylish vampire. He was a knew discovery for me in Italy. I bought many of these trade paper backs from the 1990’s. Dark without being morbid, this is the type of superhero the English Romantics might have dreamed up.

In the Dust of This Planet

This book of pessimistic philosophy mysteriously leaped into my life at the end of a grim year. In short, take Schopenhauer’s category of the World-in-Itself and add eco-cataclysm, the result will be an examination of the inconceivability, the inhumanity of the planet (Thacker distinguishes between the terms Earth, planet and world; planet is the non-human version). Given the seeming inevitability of catastrophic climate climate seems like this is a must read for anyone having trouble conceiving of a world without us.

This book of pessimistic philosophy mysteriously leaped into my life at the end of a grim year. In short, take Schopenhauer’s category of the World-in-Itself and add eco-cataclysm, the result will be an examination of the inconceivability, the inhumanity of the planet (Thacker distinguishes between the terms Earth, planet and world; planet is the non-human version). Given the seeming inevitability of catastrophic climate climate seems like this is a must read for anyone having trouble conceiving of a world without us.

Sentences and Rain

Full disclaimer: Elaine Equi is my favorite living poet. What she writes is what I like about poetry: unpredictable humor and masterful brevity. My favorite from this collection is the Tu y yo Spanglish poem that ends:

in English

the informal you

is “Yo”

This is a great collection that I come back to often to laugh, nod and feel that despite a turbulent 2016, there’s still a safe home.

“I came to language only late and only peculiarly. I grew up in a household where the only books were the telephone book and some coloring books. Magazines, though, were called books, but only one magazine ever came into the house, a now-long-gone photographic general-interest weekly commandingly named Look. Words in this household were not often brought into play.”

This is how “The Sentence Is a Lonely Place” – a speech given by Gary Lutz at Columbia University in 2008, later published in The Believer – begins.

I believe this essay still offers an alternative level of reading text. What particularly strikes me is Luts´s concept of the “topography” of a sentence, and while never explicitly saying so, he refers to the shapes of sentences via the letters and words chosen.

For example, describing a short story by Christine Schutt, Lutz begins to enumerate the symmetry of the phrase “acutely felt, clearly flat” right down to the letters in the words chosen:

“But what is perhaps most striking about the four-word phrase is the family resemblances between the two pairs of words. There is nothing in the letter-by-letter makeup of the phrase ´clearly flat´ that wasn’t already physically present in ‘acutely felt’; the second of the two phrases contains the alphabetic DNA of the first phrase.”

Later on again, he notes the physical form of the letters within this paragraph:

“I once saw a man hook a walking stick around a woman’s neck. This was at night, from my mother’s window. The man dropped the crooked end behind the woman’s neck and yanked just hard enough to get the woman walking to the car.”

While you might notice the repetition of certain letters in the excerpt, I would have never gone to the imaginative lengths that Lutz does:

“The w seems warily feminine; the k seems brashly masculine. In the fourth and final sentence of the paragraph, the two characters mate and marry in the unexpected but beautifully apposite participle winking, a union resulting in what is in many ways the most stylistically noteworthy word in the paragraph.”

While this may seem like a stretch – particularly their marriage – it seems nearly undeniable that once you begin reading with this kind of scrutiny of letters, it becomes difficult not to notice “verbal topography”.

Lutz, as he recognizes, is looking for a certain type of fiction, quite the opposite of a page turner. This would also be the antithesis of Karl Ove Knausgaard´s prose – at least in the English translation – as Ben Lerner so astutely observed.

Truth is, I like page-turning prose and don´t dwell enough on as many pages as I would like – especially after my experience with the Knausgaard books (if that is the author´s not the translator´s style, as Christopher Eva suggests in his response to Lerner´s review). Yet, I think giving the scrutiny poetry often demands of a text fits well with this idea of the topography of words, as well as what Lutz calls “lexical inevitability”.

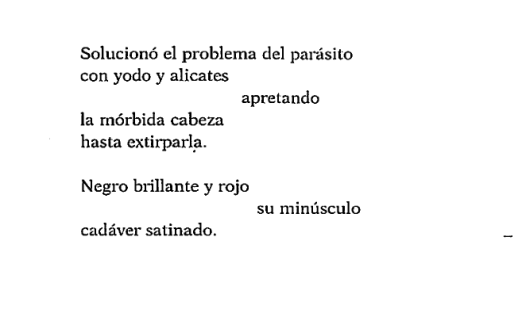

When I first began translated in the work of Spanish poet José Daniel García, I began to look for equivalency of effect in the “topography” of lines.

This is JDG’s version:

“El veneno florece en la burbuja.”

A word-for-word translation looks like this:

“The venom flourishes in the bubble.”

I think we can hear and see the “lexical inevitability” in this line from his poem “Cuerpo Tendido”. On the imagistic level JDG employs the “venom” and the “bubble” – linked with the resonance of “flower” in “flourish”. The paradox contrasts with the idiomatic level of this line: a dismal and ephemeral phrase.

If we begin to apply Lutz’s topographical approach the line becomes much richer. In this reading the flat, low-lying “venom” rolls into the stalky word “flourishes” which we imagine curling inside the round “bubble”. Where can we see this? Well the “fl” of flower, here present in “flourish” looks something like a flower growing from its stem. The round bottom of the three “b”’s in bubble resembles the round shape of a floating bubble. In this case, even the literal translation reflects the “lexical inevitability” that Lutz praises.

In other cases, however, the rudimentary word-for-word translation won’t suffice.

In one untitled poem from JDG´s collection Coma, we perceive a series of fast, clear images regarding a nameless figure; the poet limits our attention to an event described in minimal detail.

The literal word-for-word might be:

He solved the parasite problem

with iodine and pliers

squeezing

its morbid head

until it was removed.

Shiny black and red

its minuscule

glossy cadaver.

Like so much of Coma the sterile tone of medical language mixes with the treacherous and grim. In this case, the “parasite problem”- a euphemism – is the removal of hard black and red bugs. In the original there´s also a great deal of ambiguity, creating that dream-like sensation that being can simultaneously be more than one thing. Also, we don´t know who exactly is removing what. Did this person “remove” their own head?

Sometimes, as David Bellos posits in his wonderful book, Is That a Fish in Your Ear?, that equivalency in translation is a lost cause. In cases like these it’s important to remember that a translation is in the end something new, as the poems original key convention (being written in the Spanish language) is lost. Therefore in a sense I pilot this new version of the original.

For me, in JDG’s compact poem, the image that most stands out to me is that of a tick – as ticks heads must be removed in order to kill them. So in thinking about this image of the tiny ticks head, I wanted to reflect this in my translation and I thought about the “topographical” level of the text. In the end I vied for this:

“Took care of the parasite problem

with iodine and pliers

squeezing

their macabre heads

until they burst.

Shiny black and red

its tiny

varnished cadaver.”

I aimed for the ambiguity of the original in not including a subject in the first sentence. This way, the reader isn’t sure who it is with the “parasite problem”.

In the second stanza, I thought that “miniscule” looked long compare to the bug itself and used “tiny” – a word that in itself is small. I also thought “tiny” might also sound like “tick”, a word that with its “k”, conjures up the spiny limbs of the parasite.

I opted for the lengthier “macabre heads” rather than “morbid” because I liked the contrast of the longer line, the the next line cut short by the “burst”. I also like “burst” because it too looks and sounds like what it is. While it’s not an onomatopoeia, its indirect resemblance creates a more subtle version of a BLAM! The b is roundish in look and sound but it ends in the hiss of an s with the finality of a t.

While perhaps cumbersome when translating some as long as a novel – as I am now – “topography” adds a new element to the translation of more condensed texts like poems but short stories as well.

My concern is that unless we are all reading on the topographic level, it will go unnoticed perhaps by many. And while I think in reading original literary texts we are perceiving that “topography” if even subconsciously, if someone were comparing an original to the translation, comparing decisions (often word-for-word) comparisons – a favorite game for those judging the “quality” of a translation – these differences or attempts at a similar lexical topography would go unnoticed.

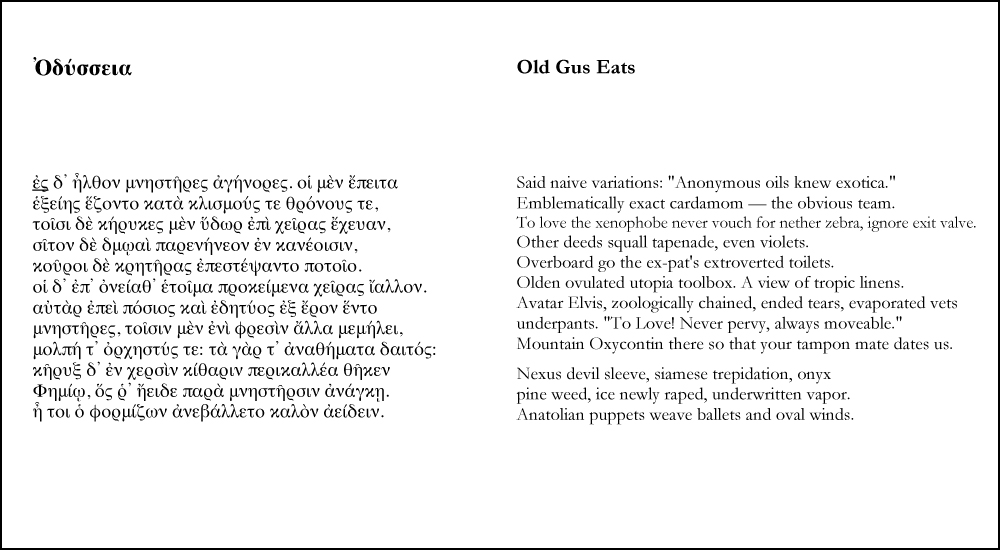

On the experimental end of the spectrum, Publishing Genius put out, Old Gus Eats, a visual translation of a few stanzas from The Odyssey. The translator Polly Duff Bresnick has no knowledge of Greek. The result is something often funny and incomprehensible. Yet, the visual symmetry between the two texts offers a different way of understanding the original.

My senior year of high school I used to frequent an all-ages jazz club in New York called Small´s. My friends and I would spend the night there, usually sleeping right through the early morning set. The musicians never bothered us and the other patrons tolerated us. Most nights there was a line and we´d have to wait until two or three in the morning just to get in. The doorman, who I also think was the owner – or so he said – used to tell us how he imagined a different kind of mass transit, hot air balloons landing on the top of the Twin Towers, which at the time, still loomed over Christopher Street.

The romantic notion of airborne mass transit has stayed with me. This might be because I still do not know how to drive, or because there’s something inherently futuristic about moving in the sky. Nevertheless, I finally found that mass transit system in the sky, quite literally, at over 12,000 feet above sea level, in La Paz Bolivia.

The cable cars system, still in expansion, travels across a series of extremely steep mountain slopes. If you were to go from El Alto (1,000 feet higher than downtown La Paz) to more recently constructed Zona Sur on Mi Teleférico, you’d have traversed a few thousand feet in a hour. Your ears actually pop between a few stops along the way.

The name of each station is written in both Spanish and Aymara. Until 1976, Spanish trailed Aymara and Quechua as the majority language. While much has changed, as global languages increasingly gain grown on minority counterparts, one still hears Aymara and Quechua being spoken in the street. Advertisements aimed at professional for learning Aymara and Quechua have been plastered on walls.

Slowly floating through the air, a motion we normally associate with amusement parks, between cragged mountain peaks, over cookouts, military school drills, a shirtless man looking peering out of his porch with a pair of binoculars, not only invites the sensation of pause, as a subway might, in its underground abyss but absolute lucidity, while the wind gently rocks the cable car.

There are however rules on this ride: paying your fare of course, and a new far for each transfer to another cable car line; not standing; only ten people in a car, and like the wonder wheel, no waiting for the next car to see if you can have it to yourself.

Like so much of Latin America, “modernization” has taken place here unevenly. While the multi-colored cable cars quietly zoom across the air, junk buses slam down pot-holed streets. The “cholas”, as they are popularly called here, seem to belong to another more formal epoch, after at some point their family left behind their traditional dress for a new sort of traditional dress, with a pollera, or long skirt, and a black fedora. They too ride the teleférico, or cable car.

Likewise, while cigarette packs have also adopted the nefariously nauseating shock photos, you can still smoke in bars. Unless you smoke, the noxious fog inside bars is a reminder of a world you are glad most other places have left behind. How did I ever do this for hours and hours on end, I wondered? Plus, walking uphill is hard enough at 12,000 feet, do we really need to add the challenge of overcoming inhibited lung capacity?

Honestly, I wish I had more time to visit bars in La Paz. I have this myth of the paceño bohemian alcoholic from some of their literature floating around in my head. Jamie Saenz is probably Bolivia´s best known poet (see he his many translated anthologies) and believed in the revelatory power of alcohol. Another write, Victor Hugo Viscarra has often been compared to Charles Bukowksi for his drunken memoirs of city streets and prostitutes – although I think this is an unfair comparison because Bukowski, in my opinion, wouldn’t have lasted as long in the cold, unpredictable streets of La Paz, drinking grain alcohol at extremely high altitudes.

Something many people don’t know about high altitudes is that they leave you with horrible hangovers. And unlike some of the other symptoms of being above sea level – stamina, for example – the high altitude hangover never goes away. At 9,000 feet a few strong beers can leave you hurting the next day. Coca leaves, some say, relieve the symptoms of hangover, but I haven’t found this to be true.

In La Paz above the tourist-travelled Calle de las Brujas, a place that evidences the power of travel tourist discourse turning a pretty ordinary street of people selling crafts into something “magical”, coca leaves are sold in large garbage bags. A coca-chewing friend had asked me to get some llipta or gipta, a sweet residue, made from quinoa or sweet potato or stevia of which add a bit of to your leaves while you chew. This sweetens the leaves and also helps breakdown the coca leaves while in your mouth.

If I were going back to the United States I wouldn’t be able to carry even coca candy with me, but you can travel freely between Peru and Colombia with it. I know people who trade leaves, as they are not marketed internationally in any formal way. Getting high in La Paz would seem to be a waste. The cable cars in the sky for me suffice. One wonders if what Jaime Saenz calls the ¨dark city¨ has transformed into something else. something more still more intangible.

Anoche viendo mi cuenta de Twitter estallar, pensé en pegar los comentarios de todos los escritores que comentaron sobre el NO en una sola página.

Edmundo Paz Soldán

No me lo puedo creer, Colombia.

Daniel Alarcón

Speechless. #Colombia

Martin Caparrós

La Paz no parece muy paisa: en el Atanasio Girardot el Sí pierde 2 a 1

Alberto Salcedo Ramos

El NO ganó porque el acuerdo fue sometido a consulta,y ese gesto patriótico, aunque hoy nos sintamos derrotados,muestra seriedad del proceso

Juan Álvarez

Es menos grave d lo q parece. Y lo es pq @JuanManSantos demostró altura democrática. Ahora los irresponsables tendrán q entrar en el proceso

¨Para mal, mezcal. Y para bien, también¨ – popular Mexican adage

Roberto Bolaño´s Savage Detectives, a great deal of which takes place in Mexico City, begins with this dialogue:

“Do you want Mexico to be saved? Do you want Christ to be our king?”

“No.”

The dialogue is taken from the end of Malcolm Lowry´s novel Under the Volcano, a novel that begins with mezcal. Not only does the protagonist, Geoffrey Firmin, have a serious problem with alcohol, he has a much more serious problem with mezcal. It´s one of the novel´s key conflicts.

Throughout the novel, he repeats to himself, in his stream-of-conscious that blurs lines between dialogue and thought and characters, “Anything but mezcal,” but succumbs anyway to that cool liquid lava. Patching it up with his wife, who has come back to México just to see if the can work things out, doesn´t happen. Instead mezcal wins. It is the volcano, or the liquid within it, that he is under.

For those who don´t know, mezcal is a distilled liquor from Central Mexico. Unlike its better known cousin, tequila—which is made from blue agave and often sugar—mezcal is made entirely from agave, the most common being espadin agave. The maguey cactus is roasted then distilled. Technically, all tequila is mezcal, but not all mezcal is tequila. That is to say, tequila is a kind of mezcal, but what is labeled as mezcal tends to come from smaller distilleries. Its taste is very different from tequila. In Under the Volcano, Geoffrey allows himself to drink tequila and points out to his companions that it isn´t mezcal after all.

Wood and fire are the first things that come to mind with mezcal for me. Lowry, a better writer of a more romantic epoch, has his protagonist compare it to “ten yards of barbed wire fence” before adding that ¨it nearly took the top of [his] head off.”

Like the craft beer scene some years ago in the States, mezcal has experienced a recent boom. While Oaxaca is the capital of mezcal, Mexico City now offers dozens of mezcalerías, where often they offer a house mezcal in addition to other varieties. Like craft beer aficionados, people tend to nerd out over them. Part of the variety could be attributed to the fact that mezcal can be filtered through nearly anything – plantain, chicken breast – opening the possibility of even great variation. The simple drink is traditionally accompanied by oranges and sal de gusano, an ashy mix of dried peppers, maguey worms, and salt. While those provide a nice break for your tongue, which will certainly tingle, the alcohol itself doesn´t really need a chaser. It´s to be sipped anyway.

There´s a moment in Under the Volcano when Geoffery´s wife Yvonn and half-brother Hugh try to convince him to eat. Standing (and drinking) in front of a great spread he hardly eats a thing, as if the food hurts him. When he wants to feel strong, like his foil Hugh, he forces down half a canapé. Mezcal has none of this effect on me. In fact, more than any other liquor I can think of, mezcal´s volcanic flavor matches dishes from Central México well.

The last few days in Mexico City, I’ve felt like an inverse of Geoffrey, about to gorge myself to death, eating five times in day and topping of the night with a visit to the corner taquería where I again marvel at the menu and try a new taco filling, in an attempt to divine the best possible plate. The way people have one more drink for the road, I´ve been eating three or four tacos there.

Maybe it’s not the food or the mezcal. Maybe I am addicted to Mexico City, although I’ve only been here a few days. I live in Colombia and while it’s not close (four hours roughly in the air) it is a relatively cheap ticket lately.

On my first week-long visit a few months ago, looking to get out of a heavy afternoon thunderstorm, I found myself in a book fair held inside the immense Auditorio Nacional. At the Fondo de Cultura Económica publishing house tables I found a discounted copy of Desde la barranca, a Mexican biography of Lowry. Naturally, it focuses mostly on his time in the country.

I learned that Under the Volcano is based on Lowry’s first trip to Mexico with his first wife, Jan, who left him in Cuernavaca, about two hours from D.F. by bus; on the second trip he retraced his steps with his second wife, Margerie. While today this seems like a scumbag move, it seems as though back then this was widely accepted, not to mention all the help his second wife gave him completing Under the Volcano, another widely accepted activity then.

Like Geoffrey, the author also struggled with alcohol, and like his protagonist with mezcal in particular. According to this biography, Lowry thought that mezcal had hallucinogenic properties, confusing it with mescaline – a common myth. Of course, if you drink enough and long enough, you´ll hallucinate regardless of what you’re drinking. I have only the most mundane experiences with mezcal. It usually arouses my appetite for something preferably in a corn tortilla, although I’m open to ideas. Yesterday I had a birria, a dish from the state of Jalisco featuring roasted goat and a soft tortilla, almost like a thin pancake, very different from the kind you normally find in Central Mexico. Alongside the dish of tortillas and goat I had a bowl of consommé so spicy I could no longer feign reading the newspaper; I had to kind of absorb it and contemplate it.

For a hard liquor it pairs with food well. So June and July for many regions of Mexico is the insect harvest. The culinary institute and gastronomical-center-slash-restaurant Los danzantes offers several dishes featuring creepy crawlies. This is not some gross out Food Network stunt. Keep in mind that indigenous groups in Mexico had eaten insects, as in many other places, for a very long time. Los danzantes also distills its own mezcal, which I found to be the perfect side car to a plate of wild rice with bugs (or arroz salvaje con bichos). The thin slices of chilies, the different textures of snails, crickets, agave worms and chinche de mezquite, or mesquite tree bug, and the earthy rice, combined with the smooth heat of the drink, had my full attention

I have done more than just indulge. When I went to the Cineteca Nacional, I didn’t think of food at all (at least not after eating the cochinita pibil torta with chipotle, avocado and onions I brought into the theater). Seeing a Mexican film while there visiting some friends, it seemed like a smart way to give them a break from me (and my eating). According to Google maps it was a simple twenty minute walk, and it was for the most part. I walked past the street where Frida Kahlo had her studio, and then where her lover Leon Trotsky, lived.

In the back of complex there is a parking lot five stories high, topped with white letters that read Cineteca Nacional. After walking through the overpass a jumbo-sized upside-down park bench appears. Had I walked in the official entrance I would have seen the ten foot high panels of famous Mexican actors that line the fence as well as the a green lawn where young people were spread out reading or lying down and talking, or smoking, or snacking.

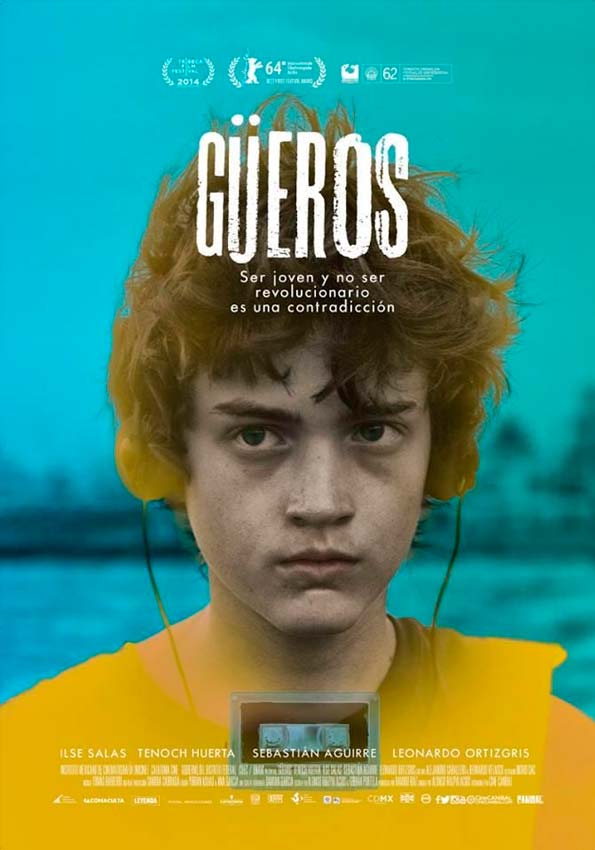

To be honest I was looking to see any production, and the show-time that worked out for me lead me to Güeros, for the matinee price of 25 pesos, about $1.50.

The first Cineteca I ever went to was actually a Filmoteca in Madrid. A friend brought me and showed me the joy of cheap, curated film cycles. After that I´ve seen maybe a dozen, the most famous one the Cineteca in Torino, and the more recently opened Cinemateca in Bogotá, none of which hold a candle to this complex that felt like a megaplex for arthouse films. There were cafes, a bookstore, a gaming shop, and restaurants. Despite the fact this was the middle of the week, in the middle of the day, young couples, a few older singletons like myself, were strolling into or out of a film.

And while the Cineteca impressed me, Güeros changed my whole day. Maybe it was the familiar neo-realist techniques (or was it French New Wave), the black and white, the hyper-stylized shots seem to beg for approval, or the fact that the film revolves around students in the Universidad Autónoma de México (UNAM) where I wished I had studied as an undergrad.

I hoped the smell of onions and chipotle on the torta I snuck in didn´t bother my neighbors; after the Cineteca showed its didactic don’t-do-this animated video, which featured someone eating a hot dog in the movie theater (a popular and condoned practice in Colombia) and others bothered by the smell of mustard.

Güeros begins when a boy, Tomas is sent off by his mother Veracruz to visit his brother, a student in Mexico City. His brother, Federico, who people called Sombra or “the shadow,” and his friend Santos are in their own words protesting the UNAM protest, namely doing nothing. They pilfer electric power from a young girl with downs syndrome in the apartment below them, until her parents find out. Tomas spends his time listening to an old rock star, Epigenio Cruz, on a cassette his father gave him, who according to Sombra could have saved “rock nacional,” or Mexican rock. After being chased out of their own apartment for stealing electricity, they set off to find Epigenio, as his younger brother insists, but on the way, stop by the occupied UNAM campus and pick up Sombra´s love interest, Ana, essentially the head of the protest movement, until her actual boyfriend, an activist, moves against her and takes over. In the end the four of them find themselves more or less on a mission, the adults taking it much less seriously than Tomas.

The title however continues to perplex me. When I told a Mexican friend I liked this film, she told me she read that Güeros was too güero. As defined at the beginning of the film a güero is “someone with light hair or skin.” In one scene, Ana takes the boys to a classy get together at a high scale bar. Ana and Sombra begin to argue and she shoves him into a fountain. He falls and pulls her along with him, then Tomas and Santos jump in. Horseplay ensues until a security guard comes over and tells them, “Hey, güeros, you can’t be in there.” Santos flips out, pointing out that Sombra (so dark he’s called sombra or “shadow”) is not a güero and that he isn’t either. The scene got some laughs and Santos’s tangent is funny, but it really made me question why the film was called güeros.

It stayed in my head on the way home. Everywhere I go here people call me güero, which aside from the chicano grindcore Brujería song I used to listen to in high school (¨Matando güeros¨ or ¨Killing güeros¨) I don´t find it offensive. Come to think of it, I don’t really find that offensive either.

But why name them for something they, as a group, are not? But then maybe this güero doesn´t really get the concept of güero. What if the definition at the beginning at the film was intentionally limited to a denotational meaning? I suppose there could be connotations of class as well in the term. But Sombra and Tomás seem to come from a relatively poor family. I was lost.

Then the film gave me an idea: if they can protest a protest, why not take a vacation from vacation? So I decided a better way to enjoy my visit was to quit acting like it was the last time I would be here, trying to bring home some piece of concrete to memorialize my trip. Instead, I would not make an itinerary or make any effort to see new places, I decided to do what I´ve been doing: drinking mezcal, eating five times a day, and going to the Cineteca Nacional a lo güero. I should say, drinking mezcal moderately; too much mezcal and I would have to use my camera to reconstruct memories.

Agradecido por haber conocido a José Daniel García en Córdoba, España.

You must be logged in to post a comment.